Scandinavian ceramics

Scandinavian Ceramics

Until the end of the 19th century Europe paid little attention to Scandinavian ceramic. Geographically isolated, a fragile sense of identity (local art swinging between European influences and national romanticism), the economic weakness the Nordic kingdoms... These were factors that contributed to it being largely ignored, content instead with copies of French and British models.

The Great Universal Exhibitions helped to change all of this. During the London exhibition in 1871 at Crystal Palace, a member of the jury complained that the talent of the Nordic ceramists “is wasted on these models which vie for bad taste and lack any specific national identity”. In answer the porcelain manufacturers Gustavsberg designed a Viking service inspired by local folklore. The movement was under way.

In ceramics, as in other domains of the decorative arts, Scandinavian designers were now charting their own course... and shining abroad. Scandinavian designers began to sign their work, inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement and by Émile Gallé, one of the first ceramists to do so, thereby making pottery a decorative art in its own right.

In 1925 no less than 45 ceramists represented the kingdom of Denmark at the Decorative Arts fair in Paris! A style was emerging, marked by a quest for formal balance, a palette often reduced to the sober colours of nature and a certain simplicity. A theme that would continue throughout the subsequent movements: neo-classicism, modernism, biomorphism (1940-1960) and neo-primitivism. The influence of Asian pottery, for its forms and glazing techniques, would prove to be longer lasting than in France.

Carl Halier pour Royal Copenhagen - 1933 & 1936 (C) Freeforms

"Folkhem": beauty for everyone

This aesthetic momentum was accompanied by a renaissance in production. Denmark and Sweden have always had a tradition of utilitarian pottery. The theories of Ellen Key and Gregor Paulsson were spreading: everyday objects should be modern, beautiful, and available to the wider population. This is what is known as the Folkhem concept: the country is home to the people, so move in! Public demand, supported by campaigns for the defence of industrial design, exhibitions and the media, helped to boost production. Owning a beautiful piece of ceramic was no longer regarded as a privilege of the elite.

This genre, to which each artist added a nuance, is today attracting a growing circle of followers seduced by its subtle variations, from Japan to the United States.

Denmark, a country of potters

A myriad of manufactures and independent workshops

Denmark may be small in size, but it has a great tradition in the world of pottery. The most recent chapters in the history of its pottery owe everything to those vibrant production sites that sprang up in the shadow of the big manufacturers such as Royal Copenhagen (1775) and Bing & Grøndhal (B & G, 1853). During his lifetime, the creator of forms (today we would call him a designer) moved between one and the other in no particular order. The Kähler workshop (Næstved), one of the most innovative, was home to Svend Hammershøi (1873-1948) – the brother of the artist – whose pieces had a certain classicism in spite of their slightly “crude” look produced using an “ash” varnish, mastic or which were, less frequently, emerald green. Knud Kyhn (1880-1969) produced animal figurines there with plenty of humour (he would also work for Royal Copenhagen and B & G). On clay-rich Bornholm island, (in the Baltic Sea), the workshop of Michael Andersen (1859-1939) and his four sons formed a bona fide dynasty, producing enamelled pieces between 1930-1950 with animal or vegetal motifs created in bas-relief antique carving. Celadon glazing (highlighted with touches of coral) was made to look like moss, while pitchers were shaped like cucurbits. Recently re-opened, the workshop now produces some re-editions.

Knud Kyhn pour Royal Copenhagen. Circa 1950 (c) Freeform

Designers before their time

Others preferred to open their own workshops. Take for example Bode Willumsen (1895-1987), who, in the 1930s, practised primitivism and brought sculpted animals to life on his pitchers. Arne Bang (1901-1983), creator of refined utilitarian objects (jam-makers, mustard makers) combined solid pleated or fluted sandstone bodies with delicate silver lids. Unheard of at that time, a woman was at the head of the Saxbo workshop in the 1930s. Nathalie Krebs (1895-1978) was a chemist specializing in enamels, which at one time were associated with the Swede Gunnar Nylund.

The sculptor and ceramist Jais Nielsen (1885-1961) worked with Saxbo for a time, but mainly with Royal Copenhagen, for whom he produced ox-blood or celadon jade pieces with grand feu enamel, inspired in equal measure by Egyptian, Persian or Chinese pottery and by the cubism that was coming out of Paris. He scattered biblical scenes into his work, sculpted in relief, for example at the base of vases.

Axel Salto pour Royal Copenhagen - 1966 & 1936 (C) Freeform

The maverick Axel Salto (1889-1961) turned away from the smooth lines of modernism. He covered his vases, the so-called germinators, sprouters or flutes, with spectacular protuberances inspired by plants, glazing them in the style of the Chinese Song dynasty (960-1279). The objects that he produced (with B & G, the Carl Halier or Bode Willumsen workshops) were pieces of art.

Bode Willumsen pour Royal Copenhagen, Vase animalier et pichet anthropomorphe - 1927. (C) Galerie Møbler

Sweden: Art deco during the pop years

At the beginning of the 20th century Rorstrand (founded in 1726) and Gustavsberg (in 1825), the two biggest manufacturers of Swedish porcelain situated in the Stockholm area, diversified into the production of ceramic art. It was difficult to ignore the other workshops and the smaller factories in attempting to forge ahead... especially given that everyone did whatever they could to attract the best artists, who would in turn train their own pupils. Art nouveau had a certain amount of success in the home of Mr. Nobel, but still remains resolutely continental in style. Revolution came to Sweden in 1917... It was at this time that Gustavsberg appointed a symbolist painter, Wilhelm Kåge (1889- 1960) to the post of artistic director. Alongside serial models for use in everyday households, this latter designed one-off originals or limited series. A dual business model that was commonly followed by almost all of the Swedish ceramists. Kåge was awarded gold at the 1925 Universal Exhibition in Paris for his neo-classical Argenta collection, a jewel of Nordic Art deco. He created a monumental urn (42 kg!), which he presented to the city hall in Paris. Amongst some of his more renowned pieces is the surrealistic Surrea series, an immaculate piece that was cut in two and stuck back together with a slight overlap.

The prolific Stig Lindberg (1916-1982) was a pupil of Kåge, from whom he took over at Gustavsberg, and in Swedish eyes he embodies the 1950s. He flooded Swedish households with earthenware dinner services produced in the workshops and created with formal freedom using hand-scarified clay in the Asian style, or avant-garde white in the 1950s and 60s (Pungo, Endive...).

Stig Linberg pour Gustavsberg, faïences peintes circa 1950 et miniatures - 1964 (C) Freeform (C) Galerie Møbler

The great Berndt Friberg (1899-1981) sits in stark contrast to the majority of his colleagues, who came from the middle classes and went to the best art schools. From a modest family of potters, Friberg started working with clay from the age of thirteen. This outstanding technician worked for a long time with Kåge as a lathe operator before showing in his own name: King Gustav Adolf was seduced by his pure monochromes, inspired by an in-depth study of Song ceramics and glazing.

Each to his own

Over at Rörstrand, Gunnar Nylund (1904-1997), a Finn born in Paris to a mother ceramist and father sculptor, imposed his own refined modernist style, before leaving to work for the Danish Bing & Grøndhal. His pupil Carl Harry Stålhane (1920- 1990) invented a great formal variety (undulations, pansies, slender...). A distinctive mark: the narrow, almost strangled neckline that opens out.

Gunnar Nylund pour Rorstrand et Carl Harry Stalhane pour Rorstrand - Circa 1950 (c) Galerie Møbler

Without forgetting Inger Persson (born in 1936), very sought after for her series of teapots, pop vases in the shape of bobbins produced in acidic shades of aniseed, cobalt blue and bright red, and the one-off originals in clayey sandstone with oriental themes (painted calligraphies, China blues).

Specific techniques

Most of the Scandinavian ceramists presented here worked with sandstone mixed with variable quantities of non-white clay, quartz and feldspar. Baked at between 1200 and 1300° C, opaque, it is extremely resistant. A Glaze (a vitrifiable waterproof coating) coloured or not, covers all or part of the piece.

Argenta

Under the guidance of Kåge, several layers of green glazing (rarely red or blue) made from copper dioxide, are applied with a sponge, then decorated with a mixture of melted silver and ceramic oil by brushwork.

The piece is baked at 640° C and the silverwork (more malleable and more sober than gold) is polished. Oxidization sometimes creates a shadow around the patterns, giving the impression that they have been encrusted. The patterns evolve: mythical characters, mermaids, geometric lines or floral patterns (1940s).

Chamotte

Several ceramists, from Gunnar Nylund to Inger Persson, have used this technique, which gives the piece a crude, rough, slightly grainy feel.

The term chamotte refers more precisely to a baked clay, crushed and sieved to produce grains of different sizes. Mixed with basic (smooth) clay components, it adds strength to the piece and gives it an undeniably rustic charm.

Rabbit fur

This degraded gloss finish, used by Gunnar Nylund, Stig Lindberg and others, takes it name from its similarity to rabbit fur.

To achieve the look, coloured pigments made from various components that react differently to the heat of the kilns are layered, and then run to various lengths along the body of the vase. This technique was already in use in China at the time of the Song dynasty (960-1279).

Persia

This cracking technique, which originated in ancient Persia, was perfected by Michael Ejner Andersen, son of the Danish workshop founder Michael Andersen. The temperature of the kiln combined with the chemical composition of the glaze produces a delicately cracked bi-coloured effect, either celadon-oxblood or white-grey. Persia was awarded the gold medal at the universal exhibition in Brussels in 1935. These pieces are often the colour of pearl.

The well-kept secrets of Swedish ceramist Berndt Friberg

To understand, you must touch. The vases and other pieces by Berndt Friberg, original works of art, have the unrivalled softness of touch of a peach, and a unique sheen. The most expensive of the Swedish ceramists, Friberg is without doubt the most accomplished craftsman. To achieve results he moved away from the methods used by his peers, who were dipping their objects into the glaze, or pouring the glaze over the object. He applied his glaze in several layers, using a method that remains secret to this day. The ceramist wrote everything down in the 1920s before his death, in a notebook that has never been revealed and which is kept in a bank! Kiln times, temperature, the quantity of smoke that is released from the kiln, oxidization in the atmosphere etc. - nothing escaped him. It has to be said that too little oxygen in the kiln can transform a superb ox-blood into a dull green-grey... His clay always came from the same source, also kept secret, in his hometown of Höganäs. What became of the notebook? A mystery…

Identifying Scandinavian ceramic

Scandinavian ceramic is generally branded and therefore identifiable. At the very least it carries the logo of the factory or the workshop, the signature of the artist or his (or her) initials. In addition, in case of a series, a number or a letter corresponds to the year in which it was produced. In reality very few one-off original pieces exist (with the exception of Friberg): it would be better to refer to very limited editions. A clue: sometimes the word "handrejad" or "handrejet" has been added, meaning hand-turned.

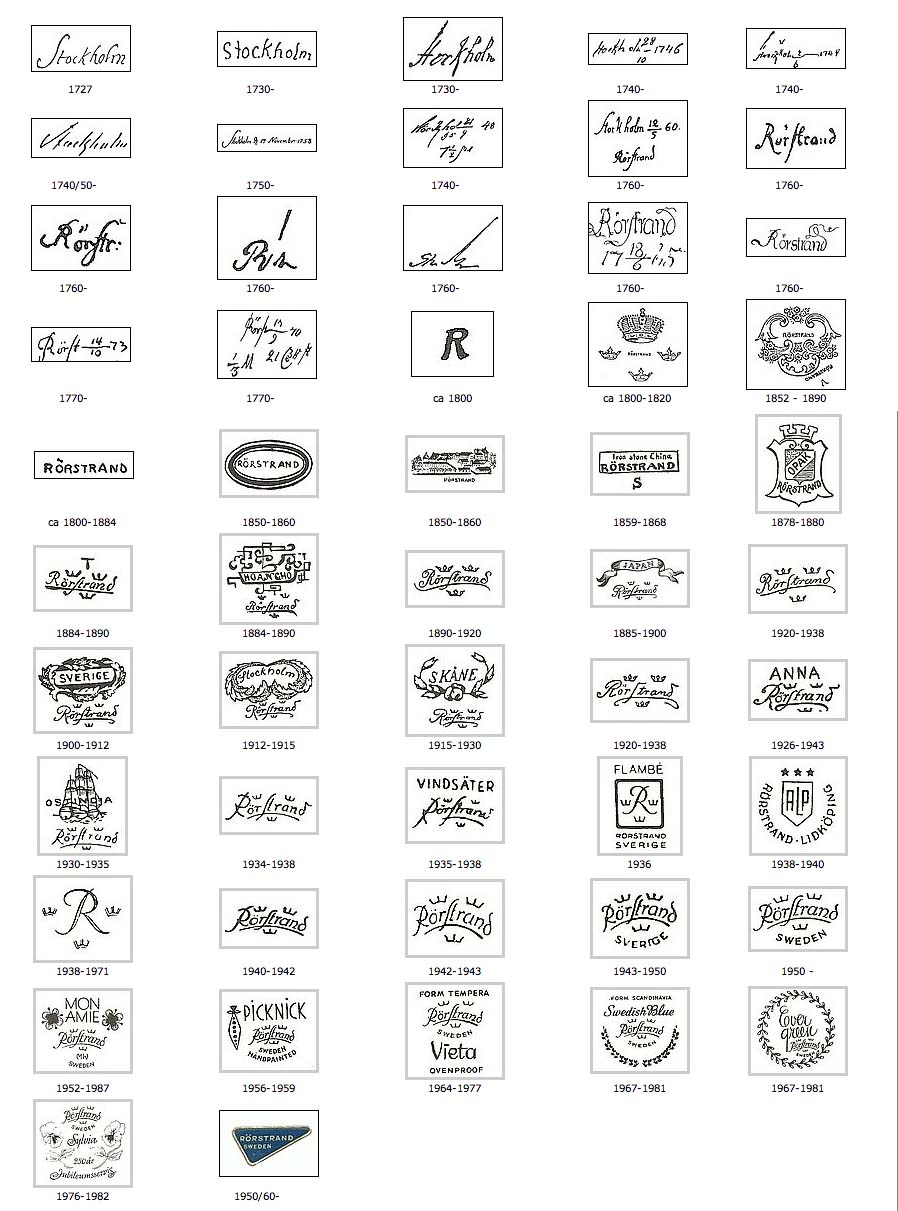

Rorstrand

Main ceramists signatures

Dating by manufacturer signature

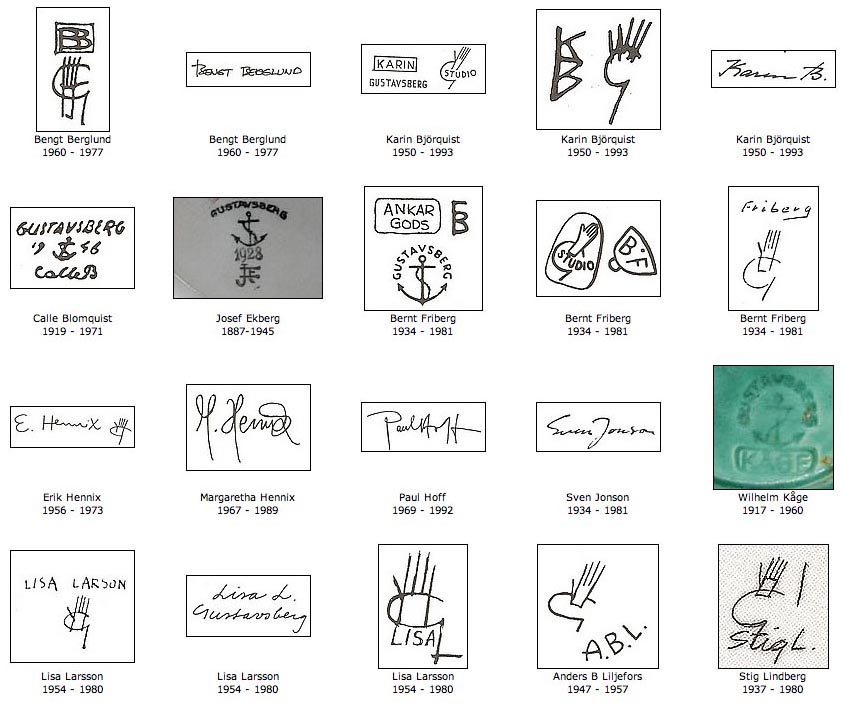

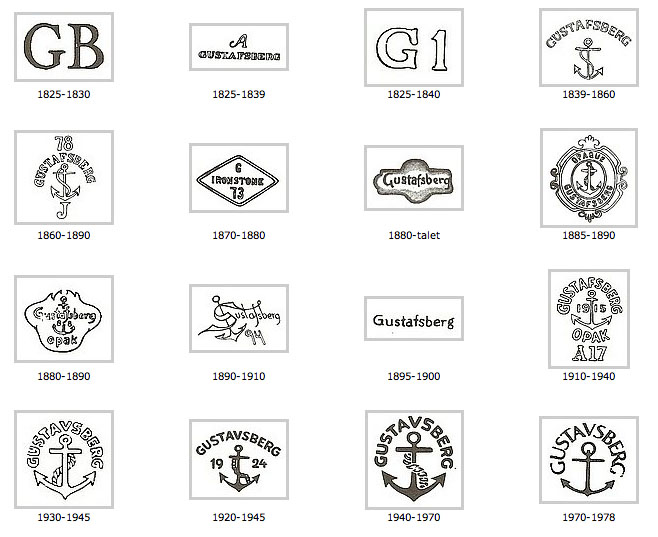

Gustavberg

Main ceramists signatures

datation par signature de fabrique

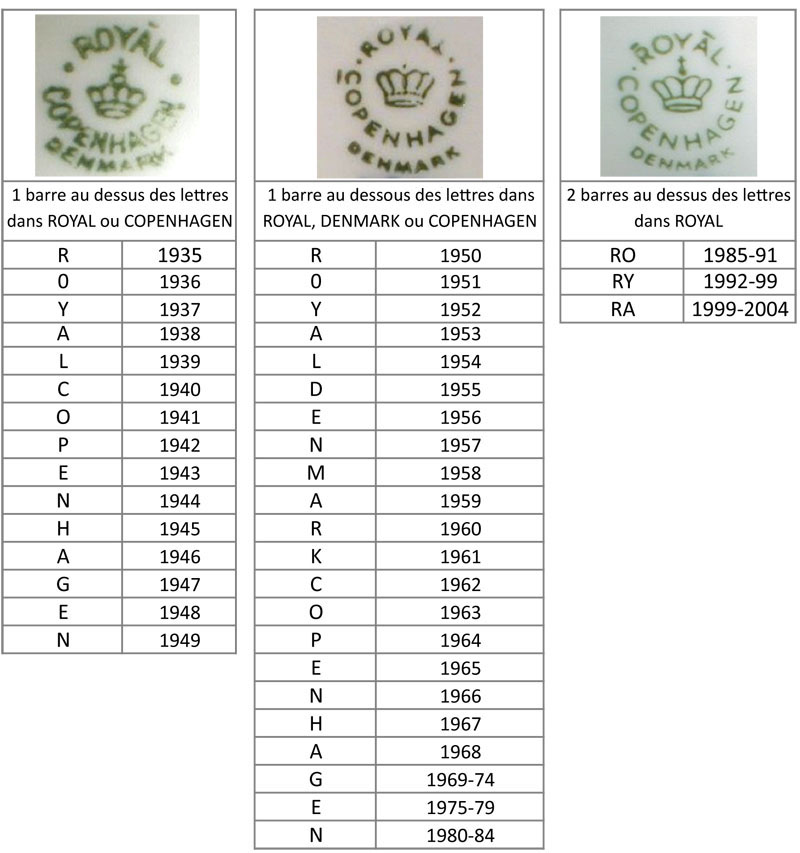

Royal Copenhagen

Main ceramists signatures

Dating by manufacturer signature

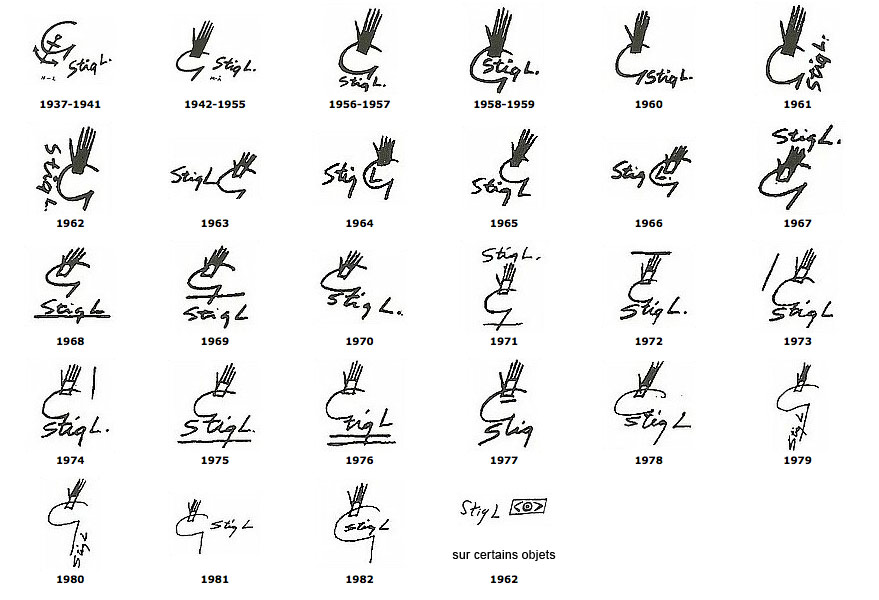

Stig Lindberg pour Gustavberg : dating by signature

(*) Litt : Alexandre Crochet for "Antiquités BROCANTE". Photos : Galerie møbler - Freeform. jamiri.dk - signaturer.se